Robert Macauley Discusses Treating Seriously Ill Kids and the Power of Honesty

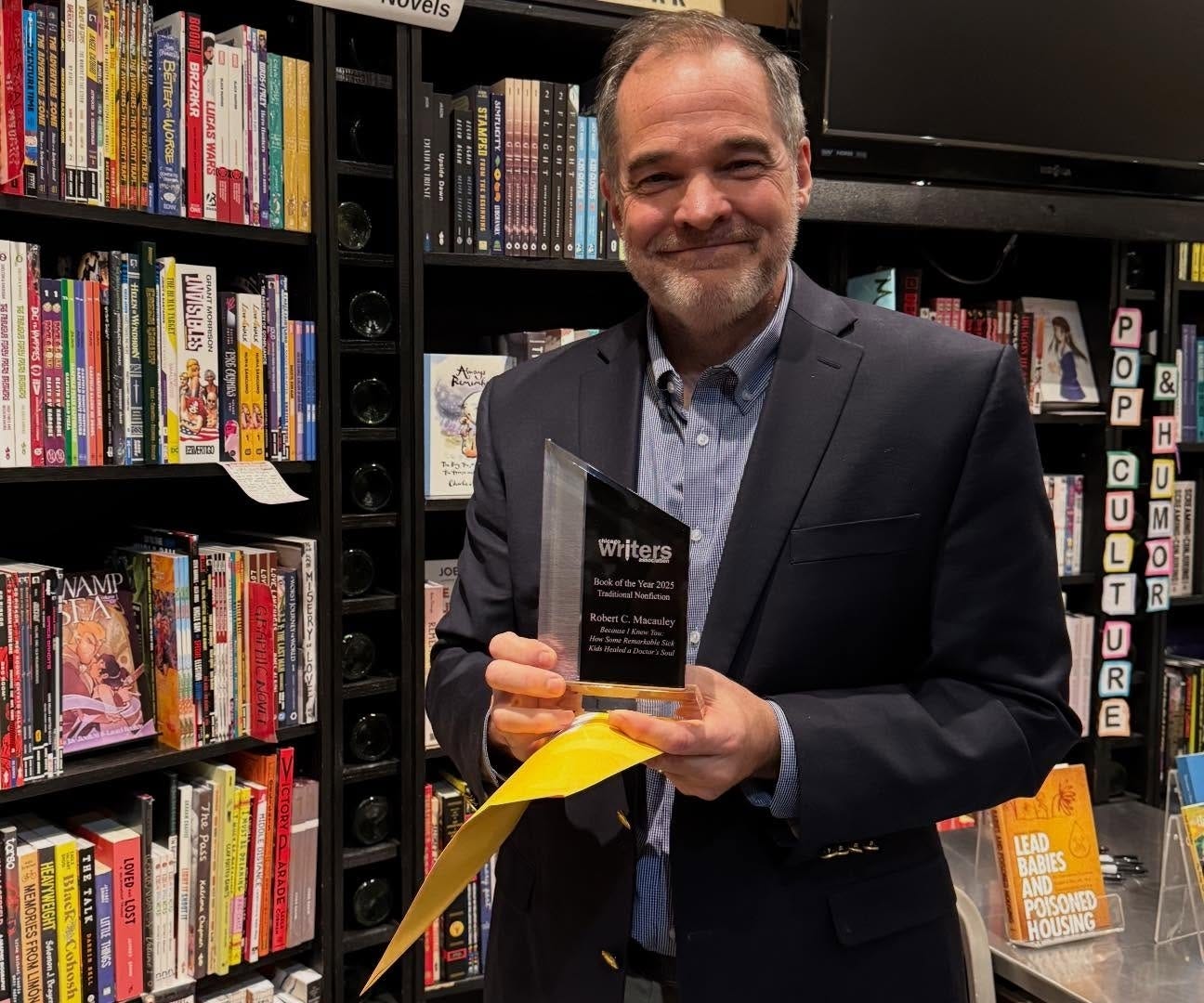

The Chicago Writers Association awarded Best Traditional Nonfiction to Because I Knew You at the Book of The Year Awards

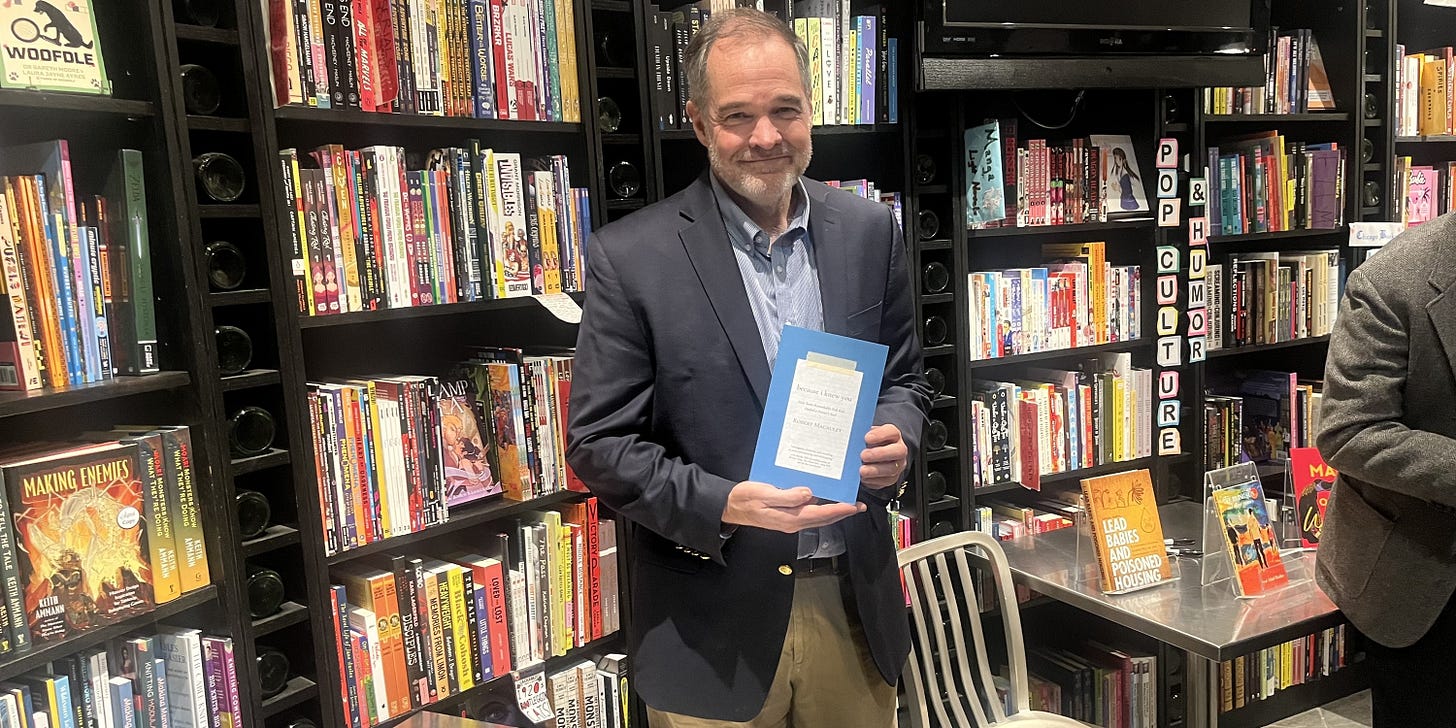

Robert Macauley choked up while reading an excerpt from his book, Because I Knew You: How Some Remarkable Sick Kids Healed a Doctor’s Soul, at the 15th annual Book of the Year Awards, hosted by the Chicago Writers Association (CWA), on Friday evening, Jan. 23.

The CWA is a collective of authors and other writers, mostly based in the Chicago area, that provides networking, bookselling and learning opportunities and promotes its members online through a CWA Member Directory.

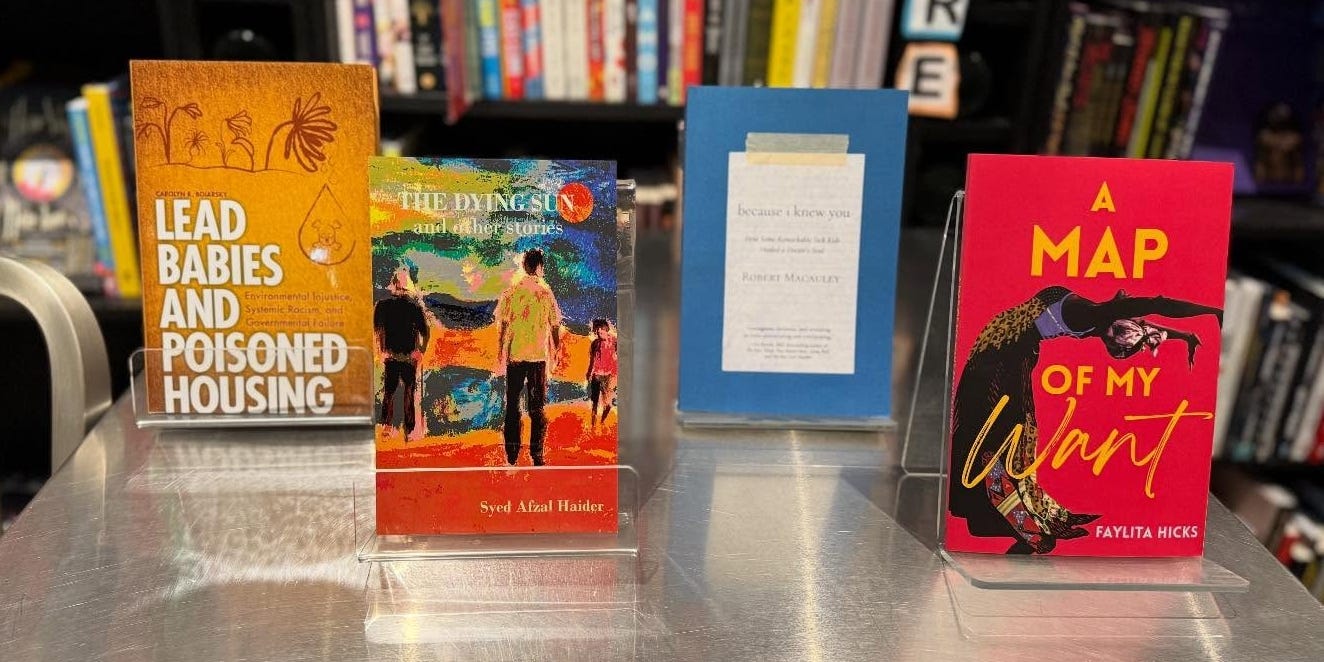

Because I Knew You won Best Traditional Nonfiction. Other awards included Best Indie Nonfiction, Best Traditional Fiction and Best Indie Fiction. This year, for the first time, the CWA added Best Traditional Poetry and Best Indie Poetry.

For a book to qualify for Book of the Year, it had to be published between July 1, 2024 and June 30, 2025. The contest was submission-based and open to CWA members and nonmembers, but nonmembers had to pay a higher fee to submit their book.

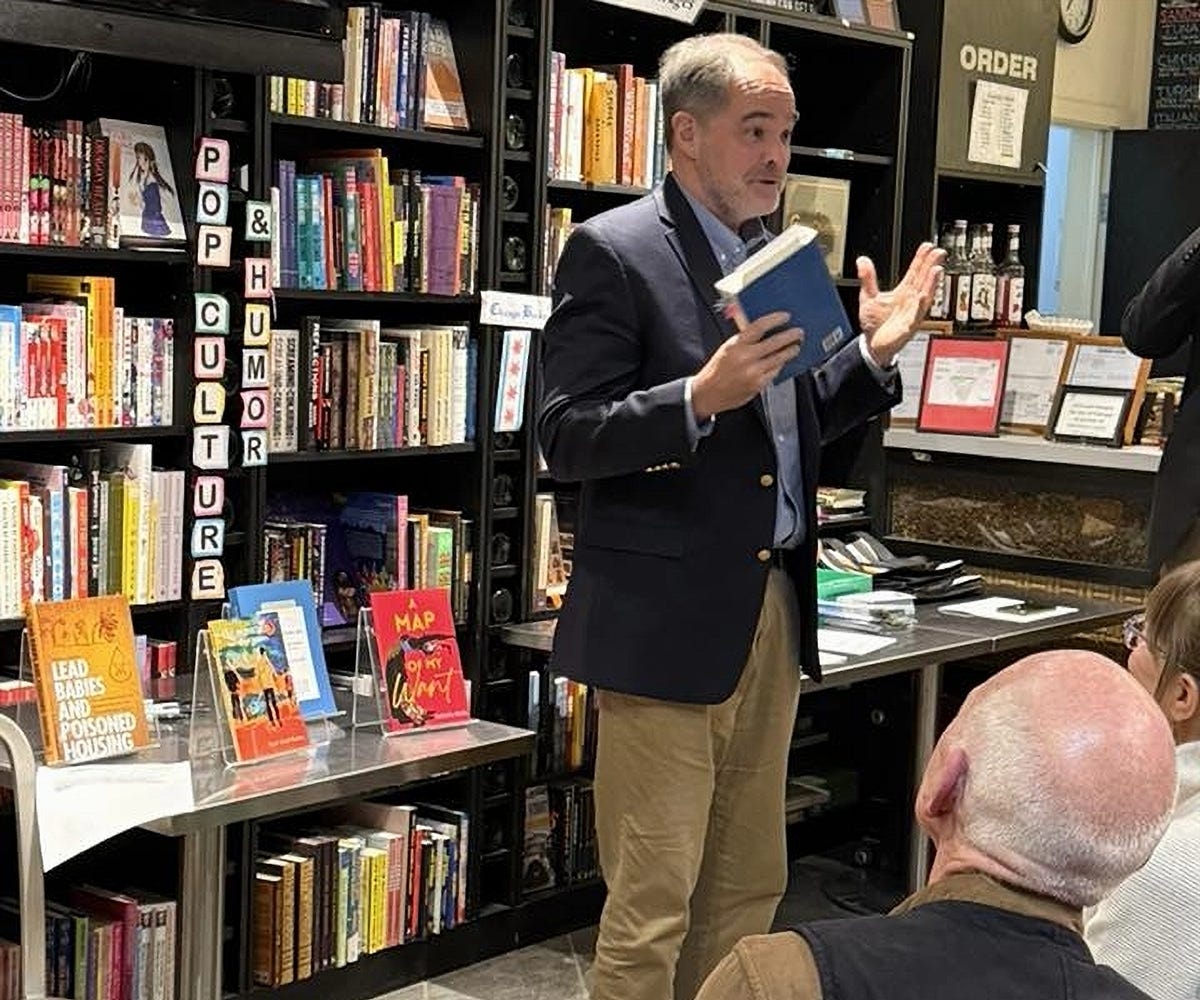

The Book of the Year award ceremony had previously been held at the Warwick Allerton Hotel in downtown Chicago. This year, it was moved to The Book Cellar, an independently owned bookstore in Chicago’s Lincoln Square neighborhood.

Several dozen people attended the event, including CWA members, other book lovers and the award winners’ friends and family. The Book Cellar served wine and lattes to attendees.

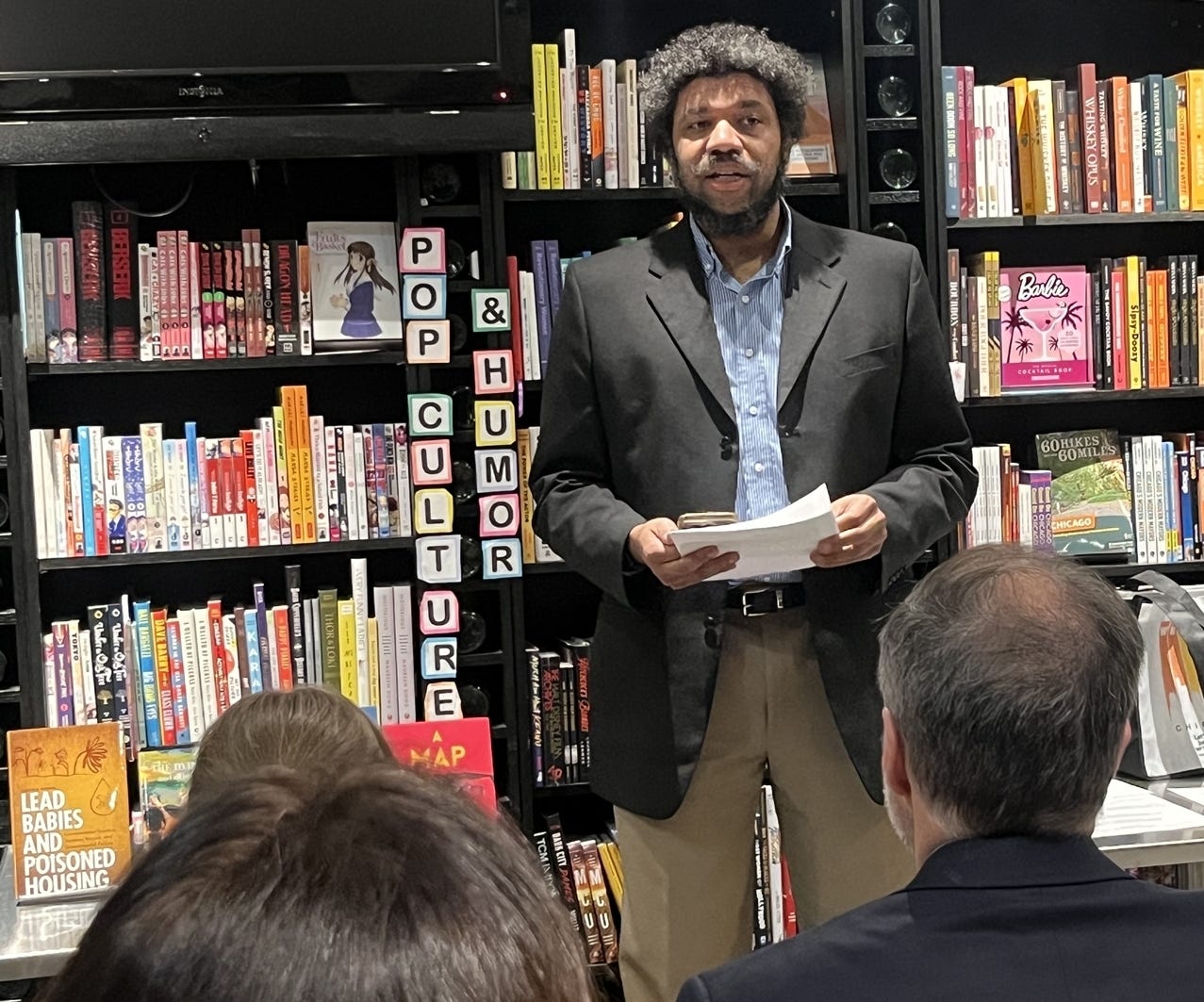

Award winners gave short speeches and read excerpts from their books.

Macauley was the last speaker of the evening. He said this placement wasn’t accidental but something he requested because of the highly emotional nature of his selected reading.

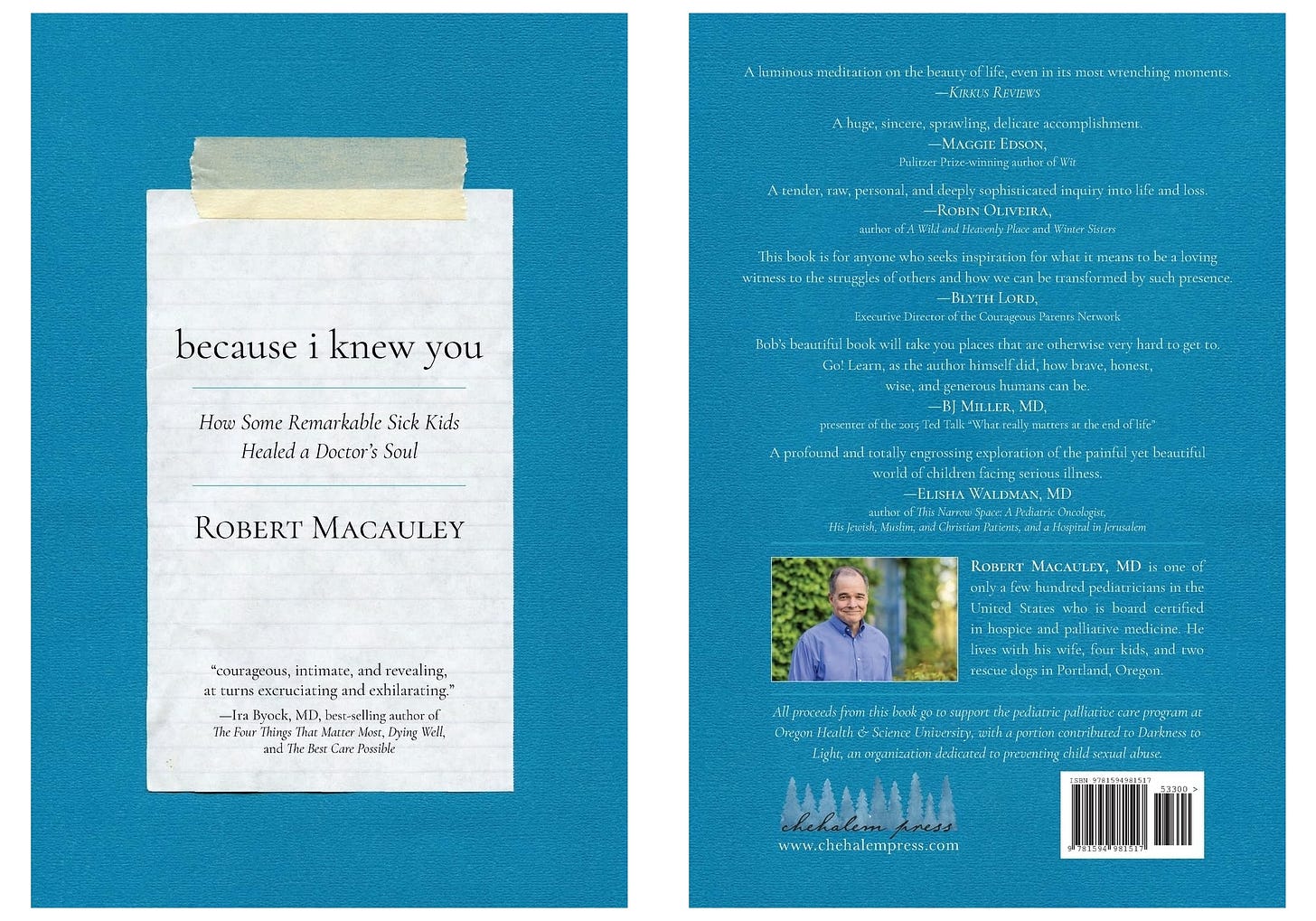

Because I Knew You, the book Macauley read from, is about his experiences as a palliative care physician who treats children, the life-threateningly ill kids he’s known, their families and how this profession helped him overcome his trauma as a survivor of child abuse.

WebMD described palliative care physicians as doctors who “prevent and ease suffering for people who have serious illnesses or who need end-of-life care.”

Macauley, a Portland, Oregon resident, has been a pediatric palliative care physician for about 20 years and practices at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland.

Macauley read aloud one of the two stories in the chapter When Hello Means Goodbye. It was about telling two parents that their unborn triplets couldn’t survive, as it was months before viability.

According to Because I Knew You, the triplets were born prematurely and lived for about 25 minutes. Following Macauley’s advice, the parents held their offspring for their entire lives, accepting the reality of their fates instead of denying it.

Macauley said he had to give these parents “the cool, hard truth,” explaining that their best option was comfort care rather than fruitlessly attempting to save the triplets’ lives. While truth and comfort can often be at odds, Macauley said in his line of work, they go hand in hand.

I caught up with Macauley about a week after the Book of the Year Awards and chatted with him on the phone. He discussed palliative care, Because I Knew You, how he feels about winning Best Traditional Nonfiction and his philosophy on truth and comfort.

Nick Ulanowski: Who am I talking to?

Robert Macauley: This is Bob McCauley. I’m a pediatric palliative care doc in Portland, Oregon, and I just wrote a memoir about the work that I do with kids who are dealing with serious illness.

Ulanowski: How do you and your colleagues provide comfort to seriously ill kids and their families?

Macauley: We have a team made up of physicians as well as a nurse, social worker, chaplain and art therapist. So, when we get involved with a patient, being that we do pediatrics, it’s rarely just the patient. It’s usually the family as well for understandable reasons. We try to get to know them really well – what’s important to them, the things that they really want to achieve, the things that they’re afraid of happening, where their sources of support come from, how they look at life and how they manage in really difficult situations.

Once we get to know them, we try to craft a treatment plan that reflects their goals and values. If the patient is having symptoms, whether that’s pain, nausea or a lot of other symptoms, we try to help with that both using medication and non-pharmacologic things. And then, we try to support them through what is really an incredibly difficult road that no one is ever prepared for because no one should ever have to walk. And we continue to walk with them down that road wherever it may lead.

Sometimes, it leads to the child’s death, despite all the stuff we’re trying to do to help them, and we support them through that. Sometimes, kids are amazing. They get better.

Ulanowski: That sounds like a tough job.

Macauley: I’ve had many parents that I’ve worked with say, “You know, you have such a tough job,” and I’ll always reply that I know of one job that is a million times harder than mine, which is theirs. I’m walking alongside them, but I’m not walking that path the way they are, because it’s not my child.

I work in academic medicine. Meaning, I work for a university. My job is not only to take care of kids, but it’s also to write articles, teach and all the other things that come with academia. And for me, that’s kind of a lifeline.

I have periods of time where I’m on duty at the hospital. We usually do a week at a time. And when I’m doing that, that’s kind of all I do. The rest of the time, when I’m not on duty, until my next week rolls around, I get to do the other stuff - the teaching and the writing. That’s very restorative for me because it lets me pay attention to myself, do a little self-care and make sure that I’m able to bring my best self to the work that I do.

Ulanowski: Still, what I imagine would be uniquely tough about a job like this is seeing this suffering over and over again. How do you manage that emotionally?

Macauley: There is a cumulative effect here. You go through one really tough situation with a family, and that’s hard. It adds up after a while.

One story I tell in the book is about a family that I worked with, probably about 15 years ago. They had a baby who was born with a very rare condition. We had to work through a lot of stuff, and he survived. He’s still alive now, living his best life, and is an incredible soul. It was really hard at the beginning, and I got to be pretty tight with this family. The dad and I got to be friends.

A few years later, we went to a music festival together with our families. We were sitting together, listening to music. He turned to me and said, “I finally figured out what it is you do.” I was like, “Well, cool, tell me. I’m dying to know what you think I do because I’m trying to figure it out myself.” And he said, “You take a really crappy situation, and you make it less crappy.” He didn’t say “crappy,” but we’ll keep it PG-rated. And I was like, “Yeah, that’s true.”

For some people, they’re like, “Well, that’s nothing.” I’m like, “No, it’s actually a really big deal.” Do I make everything all better? No. Do I take away everyone’s sadness? No. But do I make something that’s so unfair and so hard a little less hard? I’d like to think I do, and I’d like to think that means something.

Ulanowski: How are you feeling about your book, Because I Knew You: How Some Remarkable Sick Kids Healed a Doctor’s Soul, winning Best Traditional Non-Fiction at the Chicago Writers Association’s Book of the Year Awards?

Macauley: I am so honored. I guess technically, by the dictionary definition, I can now call myself an “award-winning author.” I guess I’m allowed to do that - not that I’m going to in casual conversation. But I’m amazed by that. I have a big imposter syndrome.

Smart people, if they have an idea for a nonfiction book, they write a proposal and they get some publisher who says, “Yeah, if you write it, I’ll publish it.” I did it the other way. I just wrote it. It’s so personal that I wasn’t entirely sure I’d be able to write it. So, I didn’t want to make a promise I couldn’t keep.

So, I wrote it, and that took a couple of years. When I was done, I was like, “Okay, I’ve got to try to get this out in the world.” I think I probably stopped counting rejections at 50 or more. I don’t remember how many I got. I tried everything - anything and everything that I knew. There was a period of time there where I was like, “I put too much heart and soul into this thing. I will get it out in the world somehow.”

If you had said to me, “Actually, you will eventually find a publisher, and you’re going to win this award from the CWA, I would have been like, “No freaking way.” So, I feel incredibly blessed.

Ulanowski: Why does Because I Knew You have two blank pages in the middle of the book?

Macauley: The intention of it was to lead the reader to a point of like, “Okay, I’ve been looking for this answer. This is the guy. He’s not the best ever, but he seems pretty well-equipped to answer it.” And then there’s nothing. And to sort of drop people into the nothingness.

I don’t have an answer. What I can do is I can enter into that suffering with them, and the injustice and the unfairness of it. If people want to write things in there, they certainly can, but it was more my intention to say that there is no easy answer. Maybe there is no answer, and I’m not going to come up with one.

Ulanowski: Tell me about the excerpt from Because I Knew You that you read at the Book of the Year Awards.

Macauley: There was a mom who came into the hospital during very, very early labor – too early and too premature for the babies to survive. And she was carrying triplets.

One option would have been when they said, “Could you try to save our babies?,” the team could’ve said “no” because it was not going to be possible. But they couldn’t bring themselves to do that. Because you have these parents who, in the course of a day, went from thinking they had four or five more months in order to prepare for their baby’s arrival to saying, “Oh my gosh, they’re coming now, and we’re going to lose them.” And it was just heartbreaking.

So, the team was all ready to go. The parents were asking for maximal treatment, and I met with the parents on a couple of occasions over the course of the evening. At length, I got to know them and told them, “There’s really no chance your babies are going to survive.” And they very understandably said, “Well, we can’t not even try.”

I ended up sharing with them a bit of a different perspective that came to me in the moment during that conversation. I said, “Look, if we go down this path, your babies are going to die, and they’re going to die in the ICU, after having gone through a whole lot of stuff. And if we choose a different path and focus on comfort, then you can hold them for their entire lives.”

It felt to me that that different perspective was very meaningful to them. They talked more and eventually decided to focus on comfort when the babies were born. And they did indeed hold them for their entire, very brief lives. During their lives, all they knew were their parents’ arms and not all the different procedures that we have to do in the intensive care unit.

Ulanowski: It sounds to me like you, ironically, chose truth before comfort by telling them the truth that they needed to hear.

Macauley: I certainly think I told them the truth. I think there are many ways to tell the truth. I don’t mean to obfuscate or say we’re playing fast and loose with the facts, but there are different ways of telling the truth.

So, one of the things we do in our work is we use big words, like strong words like “death.” We don’t use euphemisms. I don’t talk about people “passing away,” “moving on” or stuff like that. We name what is going to happen. And I think that’s really important because otherwise people may misunderstand, or we might sugarcoat something that deserves to be spoken plainly and understandably.

One of the things that sometimes people think is that truth and comfort are two different things. Like, you have to choose one or the other. You can be really sweet and sugarcoat things, and that’s the comfort side, or you could be blunt and speak the cool, hard truth, which is the truth side. I don’t actually think that they’re diametrically opposed. I think there are ways you can speak the truth in an unkind fashion. I certainly would never want anyone to do that. But I think that if we try to sugarcoat things or soft-pedal things, then I think that ends up leading to more suffering because people may misunderstand.

It also overlooks the fact that there’s no getting away or avoiding the fact that this is terrible stuff. Like, parents are supposed to have babies that outlive them, that they care for through their childhood and that they watch grow up. That’s what’s supposed to happen. Sometimes it doesn’t, and that’s awful. And if we try to not acknowledge that or try to make it seem like it’s not so bad, then I think that, first of all, it’s not very truthful. And second of all, I don’t actually think that’s very comforting because parents and kids, they understand way more than I think we give them credit for.

The number of times someone has said to me, “These parents, they just don’t get it.” I’m like, “No, I think they get it.” I just think they’re having a hard time processing it because their heart’s breaking. So, our job is not to force them to confront something. Our job is to walk with them as they come to understand this thing that we’ve told them.

Ulanowski: Well, Robert, thank you for your time, and have a great rest of your day.

Macauley: Thank you so much, Nick. I really appreciate it. You’re welcome. Have a good one.

If you enjoyed this interview, you can tip me on Venmo. My Venmo username is @Nick-Ulanowski, and the last four digits of my phone number are 8844.

What a great article! Fabulous job